© Jim Low

Thomas James was known as The Blind Teacher. For over thirty years, he travelled many kilometres throughout Victoria, despite having never seen the Australian landscape through which he travelled. Whether negotiating his way along suburban streets and laneways, or along country roads and dirt tracks, he travelled with a faithful companion, a dog which he had trained to guide him safely.

This itinerant, home teacher travelled by train or coach, and when these forms of transport were unavailable, he walked the distance, despite its length. Thomas James’ motivation was very simple. He sought out all those who were deprived of sight like himself, aiming to teach them how to read and write. On his back he carried a variety of books and resources to accomplish this task. His books were funded by money which he raised through public subscriptions and the support of generous citizens who realised the importance of his work.

Thomas James was born on 16 May 1835 in St Just, Penwith, Cornwall. Like his father Andrew and brothers, he became a tin miner. In 1857, after having already worked as a miner for at least six years, he was seriously injured in an underground, mining explosion. He lost his eyesight and his right hand. In later life he reflected on the immediate outcome of his accident, saying:

‘I was miserably lonely after I got well. I could not read. I had nothing to occupy my mind. Everybody was at work around me.’

Fortunately, an itinerate, blind teacher was soon to arrive at St Just. He taught Thomas how to read using Dr Moon’s raised alphabet system. As Thomas again reflected:

‘This man told me of the comfort it was to him and volunteered to teach me. I jumped at the chance and soon mastered the system. There were no more lonely days for me.’

In 1867 his father Andrew decided to emigrate with his son to Australia. His wife had died in 1855 and some of his sons were having success on the Ballarat goldfields in Australia. Perhaps Andrew worried that when he died Thomas would be left on his own to fend for himself. Or perhaps he just wanted to give him a fresh start in a new place.

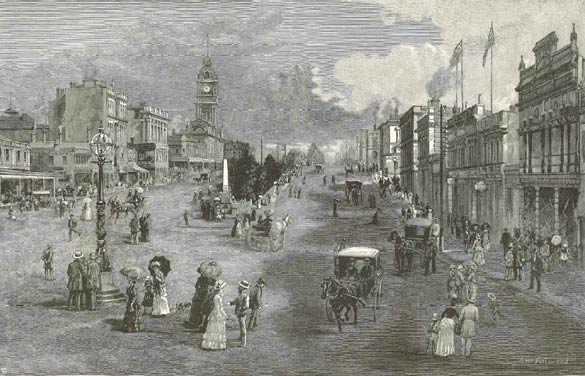

Father and son arrived in Victoria in January 1868. as unassisted passengers on the Southern Cross. Before leaving, they had to secure financial assurances that guaranteed Thomas would not be a burden when he lived in Australia. With hindsight, there is obviously a distinct irony in that! They settled in Ballarat where the other family members already lived. Thomas was 32 and his father was 77 on arrival. Unfortunately his father died in December 1869.

Thomas had a dog to help him with his mobility. But he again started to feel the despair he had experienced in Cornwall of not being fit to do anything except beg, which he refused to do. Then, as he was later to say, ‘The thought constantly came to me that I should try and teach the blind to read.’

Thomas had brought with him some of his books and the resources to teach Dr Moon’s raised alphabet system. He heard of a person who was blind and quickly made contact with him. ‘The mutual pleasure it gave us,’ he recalled, ‘spurred me on to look for others. In a few months I had a circle of ten or a dozen. Two or three were in the Benevolent Asylum.’

As the raised lettering in his books began to flatten with their increased use, Thomas successfully approached a local citizen for financial help to buy new books. He also gained interest and assistance through newspaper reports and letters about his public subscription to raise funds.

Thomas James vocation to teach the blind to read and write had now begun in earnest. As well as raising funds to keep up the supply of books to his increasing number of readers, he helped by making his own teaching resources, no mean feat for a man with only one hand. He continued to travel extensively around Victoria seeking out new candidates to teach in their homes, as well as collecting and exchanging books with those already under his charge. He also learnt the Braille system of raised dots from another sightless man. He could then offer both methods to those whom he taught. His library of books continued to grow in number and variety. Being a devoutly religious man, his early collection of books had favoured Biblical content. Over the years the collection diversified to meet the varied interests of his readers.

Thomas James arrived at the Aston household in Carisbrook, not long after Mr Aston’s death in 1881. His visit would have been prompted by the information that one of the Aston daughters was now blind.

The daughter was Tilly Aston, born in 1873 with impaired vision and completely blind by the time she was seven. Tilly went on to become a writer and poet, a teacher of the blind and a wonderful champion for many benefits for the blind. She wrote in her Memoirs, recalling the visit:

‘One day there appeared at our door in Carisbrook a very interesting stranger. He was tall and sturdy, loud-voiced and sociable, with a broad Cornish accent that had the cheerful up-and-down intonation of the cousin-jack dialect …I can recall his earnest voice as he prayed for the little maid, for her mother in widowhood, that both should see the light of God’s face through and above all troubles, and that my blindness should prove rather a source of love and joy than a burden and a heartache.’

Thomas James received an enthusiastic welcome from the Astons, staying the night to give him time to introduce Tilly to the Braille method of reading and writing. As she said in her Memoirs: ‘He left the wherewithal for me to continue my studies.’

Tilly also remembered the ‘intelligent and friendly canine offsider’ who accompanied Thomas James. This retriever, who was called Fido, had been trained by Thomas. The dog was considered by his owner to be ‘the most intelligent dog I have ever had…When he had to guide me over a busy crossing he would turn round, take the leading strip in his mouth, and walk sideways, instead of pulling straight ahead, so that he could see no harm befell me.’

In later life Tilly Aston experienced criticism from people who believed that teaching the blind was not as effective when practised by a blind person. She would have seen such cruel prejudice for what it was. She knew the blind could successfully teach the blind, her own experience and that of Thomas James surely made nonsense of that.

Over many years and across many kilometres, Thomas James quietly went about his important work. He sought out the sightless, freely taught them to read and write and, of course, offered them his comforting friendship. When recently reading J. Wilson’s centenary history of the Association of the Blind titled No Sight – Great Vision (1996), I was disappointed to see only a single, fleeting reference to Thomas James and his achievements.

Thomas James passed away on 7 November 1915 and is buried in the Ballarat New Cemetery. The last words should be given to Tilly Aston. In her opinion Thomas James was ‘a good and devout man.’

© Jim Low

Listen to Jim’s song, His Name was Thomas James