When those shots resounded

Bodies lying on the bushland floor

They crossed a line and forever

Their name would be outlaw

In late September 2015 I travelled to Mansfield for the first time. I wanted to visit this town in northern Victoria to observe how the town remembers Ned Kelly and his gang of bushrangers.

It was from Mansfield that four local policemen travelled into the nearby Wombat Ranges in an attempt to find and capture the bushrangers. Only one of the policemen returned to Mansfield alive.

In the centre of Mansfield, occupying a large, traffic roundabout, is an impressive memorial to the three, Irish-born policemen who lost their lives when shot by Ned Kelly at Stringybark Creek. Kelly was twenty-three years old at the time of the shootings.

On the memorial is written:

To the memory of the three brave men who lost their lives

while endeavouring to capture a band of armed criminals

in the Wombat Ranges near Mansfield

The tragedy commemorated by this memorial happened almost one hundred and thirty seven years ago. A fresh bunch of flowers at the foot of the memorial reminded me that I was there only one day after the National Police Remembrance Day. On this day Australians are encouraged to reflect on those members of the police force who have lost their lives in the line of service. I was able to read partially the card that accompanied the flowers:

Staying strong … in memory of our fallen …

Above the flowers was a tablet on which the following words were engraved:

Three Victorian Police members were murdered at Stringybark Creek near Mansfield on the 26th day of October 1878 by a group of men who came to be known as the ‘Kelly Gang’.

The tablet goes on to inform us that the memorial was erected in 1880 ‘to honour the slain police’ and that the three policemen are buried in the Mansfield Cemetery.

I went out to the cemetery to look for their graves. This well-cared for cemetery is located in a picturesque part of the town, surrounded by low lying hills. The first grave I came across was that of Police Sergeant Michael Kennedy. He was 36 years of age when he was, quoting from his headstone, ‘cruelly murdered by armed criminals in the Wombat Ranges’. The headstone continues its tragic narrative, informing the reader that Kennedy ‘died in the service of his country, of which he was an ornament, highly respected by all good citizens, and a terror to evil-doers.’ The only one of the policeman who was married, his wife Bridget Mary is buried with him. She died in November 1924, aged 75.

I then found the graves of Mounted Constables Michael Scanlan (35) and Thomas Lonigan (34), whose headstones inform us that they died ‘in the execution of duty …murdered by armed criminals’. The three memorial headstones were erected by the Victorian Parliament.

While at Mansfield I visited the tourist centre.

I noted that there was nothing on display that gave any prominence to Ned Kelly and his gang. Also absent were any books relating to bushrangers. Glenrowan this definitely was not!

Over a late breakfast, I reflected on what I had seen. There appeared an unquestioning abhorrence of the crimes committed at Stringybark Creek by Ned Kelly, who was described unequivocally as a murderer and criminal. I appreciated the dignified way the town honoured the memory of the three policemen. There was no way this town could be accused of glorifying any memory of Ned Kelly legend.

On the way to Mansfield I passed through the little town of Swanpool. There the Kelly narrative was remembered differently from what I later discovered in Mansfield. At the local garage, a painting of a rather questionable looking, metal-hooded head of Ned Kelly covered the curved surface of a large, concrete water tank, Ned’s eyes gazed towards the heavens, with an uncomfortable vacancy.

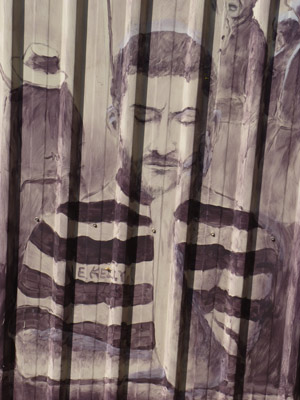

On a colour-bond fence adjacent to the tank was a mural featuring sepia-toned scenes from Ned Kelly’s short life. The surface of the fence gave the impression that you were looking at everything through the bars of a gaol. As well as a picture of Ned in prison garb and one of literally his last stand at Glenrowan, there was a depiction of Stringybark Creek. There Ned appeared with the lifeless bodies of the policemen. Described in a nearby caption as ‘The Stringy Bark Creek Shootout’, the accompanying text was sympathetic to Kelly saying ‘he is compassionate for his fellow man’ and that ‘he was very sorry that these men lost their lives’.

Returning home, I again reflected on some of the things I had seen, considering in general how we represent ‘our heroes and villains’ who are scattered about in our history. Sometimes, we effortlessly seem to condone and even trivialise blatant wrong-doing, for the sake of the narrative we desire to tell.

Australia’s history is full of violence and conflict. The way it was occupied originally by Europeans resulted in conflict, suffering and death. The many and varied memorials to wars, fought in other countries, further consolidates the violence of a past that we rigorously strive to remember.

I read again Ned’s rambling words in his Jerilderie Letter.

His conclusion, for example, that:

it was cowardice that made Lonigan and the others fight it it is only foolhardiness to disobey an outlaw as any Policeman or other man who do not throw up their arms directly as I call on them knows the consequence is a speedy dispatch to Kingdom Come

I reflected on the anger, bitterness, contradiction, illogical argument and megalomanic claims and demands that soured his words throughout the letter. The morality of violence seems to have eluded his narrative. And sometimes our own retelling of history falls into the very same trap.

© Jim Low

October 2015