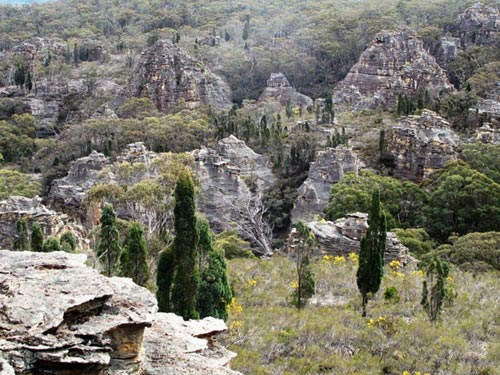

“If I wanted to get there, I wouldn’t start from here” is the punchline of an ancient joke about an Irishman giving directions to a tourist. Almost as ancient are the laudable objectives on this signboard about the 1995 project which could yet be the jumping off point for the transformation of the southern Newnes Plateau into one of Australia’s finest and best presented natural area experiences – a project aptly named Destination Pagoda in its new incarnation (see article in Blue Mountains Conservation Society’s May Hut News, page 2).

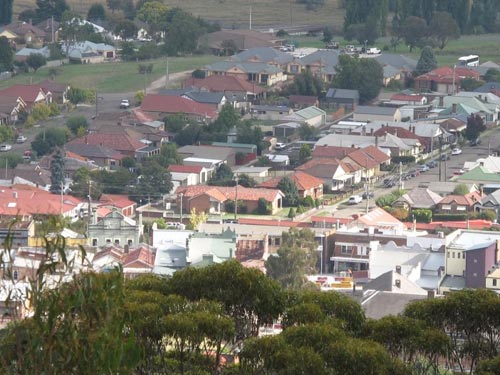

If you want to get to the finest views of pagodas in the Lithgow district, there’s no choice but to start from State Mine Gully. On a school holiday Wednesday in April 2019, Hut News noticed steady traffic which included standard two-wheel-drive vehicles making their way up and down the shockingly deteriorated escarpment road that connects the Newnes Plateau with State Mine Gully. Many of the drivers were protecting their vehicles by taking ten minutes to do one kilometre.

But this is the only viable access route for most of the plateau’s scenic delights that does not cross private property. It is the only route that truly allows the community of Lithgow a sense of ownership of the most ecologically and geologically diverse part of the town’s hinterland.

At the site of the old rehabilitation project, you are confronted with numerous expensive changes that would still need to be made to convince the visitor that this is one of Australia’s most significant natural area gateways. The broom and blackberry plants, along with other weeds, need to disappear. The hardy Mountain Ash trees need their retinue of Banksia and Leptospermum understorey to swell. The discarded sleepers and rails from the old branch line need to be incorporated into the generally well-kept railway museum. And the picnic benches need to look capable of accommodating modern-sized posteriors without fracturing. It’s fortunate that Destination Pagoda has harnessed such experienced and dedicated activists – all our energy will be needed.

© Don Morison