© Glenda Bone-Gaul

World War 2 brought many changes to Australian households. On a practical level it brought shortages that affected normal domestic life. These shortages had to be worked around and great imagination had to be used in order to cope with the lack of food, clothes, petrol and so on. The role of women in the home became much harder, their usual routine had to be contoured to the changes War brought. The lack of manpower was felt in many ways and women had to make up for this shortfall. Some women coped better than others. This is the story about one such woman and how she dealt with the changes that War brought to her home.

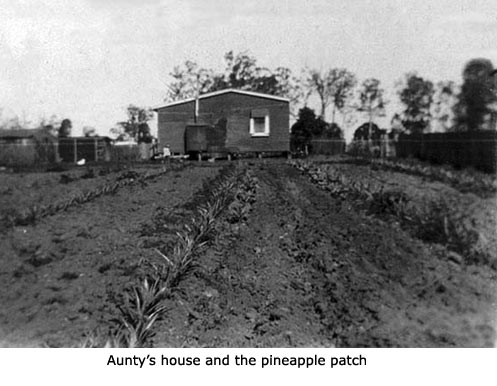

Edith Williams, born in 1893, was my great aunt. At the time of WW2 she was unmarried and living with her widowed Mother, Emma Williams (nee Brownlow b. 1856). Edith nursed her mother at home right up to her death in 1946. As Edith never married it meant she was used to running her own household, so in that respect she was probably better off than other women as she did not have to adjust to a life now minus a husband, as they did. Edith owned 5 acres of land which she had totally cultivated with crops of pineapples, corn, citrus trees, grapevines and so on.

She also had poultry and of course her beloved horse, Dolly, used to pull Edith’s buggy, her mode of transport in those days. In today’s terms she had her own cottage industry, which provided a home and its comforts for her and her mother. Her life was extremely full and War was to bring an even fuller life to her doorstep, quite literally.

The suburb where Edith lived became one of the main camps for the American troops. In those days the Pine Rivers Shire consisted of approximately 4,500 residents and by War’s end 15,000 soldiers would have been bivouacked there. Australian soldiers were also camped there but not in such great numbers as the Americans. This camp was not more than half a mile from Edith’s home, so she looked for a way to make this influx of activity in her community work to her advantage. This she did by making the decision to set herself up to do laundry for the soldiers. Comparing how we do laundry now to how it was done back then, it makes you wonder where she got the time and the strength as she already had a very full life.

The following has been formed mainly from my Mother’s memories of this time, and from information taken from her autograph book, which I will elaborate on shortly.

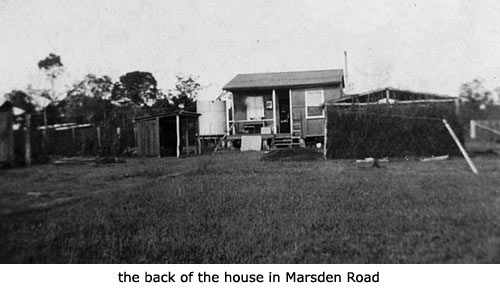

Edith Williams’ home was modest. She had a very small laundry room detached from the rear of the house, not nearly big enough to do large amounts of laundry in, so she set up a tent in her back yard and this became the center of her laundry activities. Inside the tent she set up trestle tables to sort, iron and fold the clothes on. Once done they were parcelled ready for pickup.

As Edith would certainly not have been allowed on to the actual camp grounds, the soldiers would have to ask for permission to leave the camp to take the laundry to her home. The camp was not more than half a mile away. Once the clothes were dropped off she would put some sort of identifying mark on them so that she knew what belonged to whom. The clothes would then be sorted, uniforms, woollens and whites – colour did not figure highly, as you can imagine. War is a drab and colourless thing.

Woollens would be soaked gently in warm water, given a gentle rub then put through the mangle, rinsed, and mangled again before going on the line. A ‘mangle’ was two rollers that you fed the clothes between while turning a handle that worked on a cog which turned the rollers. The clothes compressed as they went through the rollers and the water was squeezed out.

The uniforms were a different matter. They would first be wetted and soaped using either Velvet or Sunlight soap, (the soap would also be broken up into smaller pieces or grated to be used in the boiler). Stains and marks would be attended to by either using a scrubbing brush or rubbing them up and down on a wooden washboard. Once this was done they were put in a laundry trolley to drain, the water collected to be used again. A boiler was set up. It was a large round tub on a metal stand set over an open fire with a metal windbreaker around it to stop any wind from blowing the fire out, and also to help prevent the fire blowing elsewhere and starting an unwanted fire. There was no water on tap in her back yard in those days so Edith would bucket the water from her watertank.

Once the uniforms had been boiled they would be taken out of the tub using a copper-stick and they would be put in the trolley again to drain. Once again the water was saved and if too dirty it would be used for the produce that she grew. Once they came through the mangle they would be rinsed then mangled again, (when the whites went through this final rinse ‘blue from a Ricketts blue bag’ was put in the water to ensure their whiteness). All water that could be saved was, and then recycled.

When they were ready for the line the clothes would be hung out on the old t-section clothes line and once full it would be propped up with a stick, with a notch cut in the top. This supported the line which could collapse from the sheer weight of the washing. Even though the clothes had been “mangled” they would still retain a fair amount of water making them very heavy to handle.

Once dry they would be taken into the tent where the trestles were set up and the folding and ironing would begin. The clothes to be ironed would be dampened and rolled up to keep in the moisture as this made the uniforms easier to iron. Edith used two different types of irons. One type was called Mrs Potts irons. Essentially it was a set of two or three irons, which were heated by putting them on the stove. One iron would be used until the heat went out of it, the handle unclipped, transferred to the next hot iron, and so the irons were cycled through so she always had a hot iron. The other type of iron used was a petrol iron, which once up and working would give an hour or so of heat per tank of petrol. When the uniforms were ready to be ironed Edith would starch them by spraying them with cornflour which was dissolved in water. Each type of iron when cooled down would have its bottom rubbed with beeswax to stop it rusting and to keep it clean.

The laundry idea took off so well that Edith enlisted her sister, Emily Walker, into helping. This entailed Emily travelling 20 miles on a bus to Edith’s. My mother, Thelma Gault (nee Walker), would accompany her mother out to her aunt’s on these working bees.

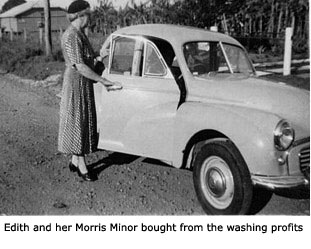

So well did the whole enterprise succeed that Edith decided that with the profits she’d buy a car, and so the saving started. Not wanting to bank the money she got Emily’s husband to make her a weatherproof container that she could put the money in and bury for safekeeping, which she did, under her mango tree. At War’s end she had enough saved to buy a new Morris Minor which she drove right up to her death in 1963.

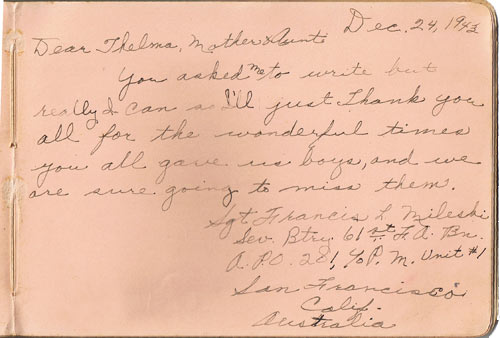

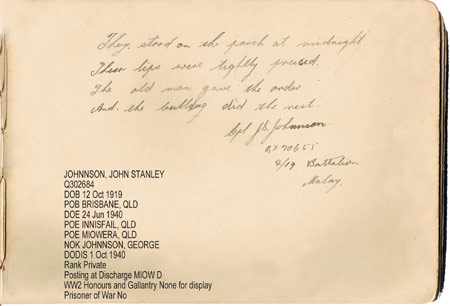

On the occasions when my Mother went to her Aunt’s she took her Autograph Book along with her and as the soldiers came to drop off or pick up their laundry, she would ask them to sign her book, which they did, including their Service Numbers and battalions. The American soldiers also signed the book and there are numerous pages where they thank Edith, Emily and Thelma for making their time spent in Australia more pleasant due to the hospitality shown to them.

On the Australian War Memorial website I read the Unit Diaries for the 2/33, in particular for the period of time that they were stationed at Pine Rivers. The Routine Orders by Lieut-Col A W Buttrose warns the men to respect private property and he pointed out that stealing of fruit, notably pineapples, must stop. In another Routine Order he warned the soldiers not to go onto the grounds of the Marsden Boys Home but if they did they would be most severely dealt with. Edith’s home was the only house near the Camp where fruit, and in particular pineapples, could be found and she would not have hesitated in notifying those in charge if she was missing produce from her garden. The Boys Home mentioned was not 500 meters from her home. I’m not sure what the soldiers would have been doing going onto the property but it brings home the point that everyday life was affected in many ways during the War years, in ways that we would never even begin to imagine. With regards to Edith’s pineapples, she used to grow the small variety and I can remember cutting them in half and being given a teaspoon to scrape out the flesh. It was like taking a bite of golden sunshine and that they may have gone missing does not surprise me as they were so delicious.

One thing Mum recalled about the uniforms was the difference in the condition of the Australians compared to the Americans. Ours were in a much poorer state which is hardly surprising I now realise as the Australian troops had already seen action overseas. In fact they were in Pine Rivers as a rest over before being shipped out again. The other thing Mum recalled was when the Americans first arrived they had corks hanging from their hats, (just like a swaggie’s hat) but when they saw “our boys” and their slouch hats, they quickly rid themselves of the corks.

It’s only recently that I have seen the autograph book, and after reading it I realise that it contains a deeply touching piece of history that incorporates the soldiers, both Australian and American, my great Aunt and grandmother’s hard work ethic. My mother’s unwitting recording of it gives us a glimpse into my family and our nation’s history.

In the autograph book along side many of the signatures Mum has pencilled in, obviously at a later date, “safe” or “killed”. I have asked her how she found out what happened to the men but she can’t recall. However on every one that she has written “safe” or “killed” it is 100% correct, as I was to learn. On many occasions Mum had said to me that the soldiers were mainly in the 2/33 Battalion and she recalled a patch on their uniform that the soldiers referred to as “mud over blood”. When I asked her what they meant by that she said it was the color of it, a brown on top of a red.

The “mud over blood” patch was awarded to the 2/33 for their participation in various conflicts. When they left Australia they went to New Guinea to reinforce the battered units on the Kokoda Trail. In fact it was the 2/33 who found the bodies of at least 75 to 80 soldiers who had died nearly a month prior. The burial of these soldiers forms the basis of “The Myth of Brigade Hill”, which basically is a disagreement over where the remains of these men lie. The Australian Government maintains the soldiers’ remains were relocated to a War Cemetery after the war ended, whilst on the other hand it is argued by a group of people, some being local villagers, that the remains were not relocated.

War is a terrible thing, yet out of adversity people dug deep and found themselves doing things that under normal circumstances they would not have contemplated. Just maintaining a normal lifestyle was something that not only had to be worked hard at but also required having an imagination and an industrious nature. Something that Edith Williams and her family came up trumps with.

© Glenda Bone-Gaul [email]

of interest

- Emma Williams was the daughter of William and Emma Brownlow of Rockley, NSW. William and Emma Brownlow were a part of the approx 600 people who fled the Industrial Revolution in France in 1848, arriving in Australia as assisted immigrants and in time these immigrants would be referred to as The Lacemakers of Calais).

- Below is a list of the men who signed Thelma Walker’s Autograph Book

The men who signed Thelma Walker’s autograph book

Here follows a list of the men who signed Thelma Walker’s Autograph Book. If anyone is related to one of these men and would like a scan of the page their relation wrote on, please email Glenda.

- J SX500267 John Arthur Wilson (Butch)(SX1165) 2/33 Btn [Mention in Dispatches … London Gazette 30 Dec 1941; London Gazette 27 April 1944; Commonwealth of Australia Gazette 27 April 1944]

NX52597 Thomas William Rutter 2/33 [died 27 Nov1942 – Port Moresby (Bomana) War Cemetery]

TX1387 Arthur Hampton. Deloraine, Tassie 2/33.

NX37094, John Charles Thompson. 2/33 [died 18 Sep 1943 – Port Moresby (Bomana) War Cemetery]

QX8255 P R Harrison. 2nd Anti Tank 6 Bty AIF.

NX60512 Pte H.A. Seidel 2/33.

NX72249 Donald Cleaver 2/33.

NX27879 James Lawrence Jack 2/33.

VX2045 Cpl J H Dwyer 2/33.

DX53 Pte Harold George Hyde B Coy 2/33.

NX79829 William John Smith 2/109.

NX68321 William John Arnold Smith.

NX37315 Harold James Edwards 2/33.

NX36495 Thomas Bowen Alderson 2/33.

NX2752 Kenneth William Golsby 2/33 [KIA 19 Oct 1942 – Port Moresby (Bomana) War Cemetery]

NX35516 Thomas William Budd

QX3836 Sgt Edward Fahey HQ Coy 2/33 Btn.

NX28825 William Gordon Jones No 3 Platoon HQ Coy 2/33. [19 Oct 1942 – Port Moresby (Bomana) War Cemetery]

NX25147 Robert Charles Williams 2/33.

QX70655 John Stanley Johnnson.

SX17333 John Patrick Forde. NX48603 Raymond Williams 2/33.

VX70742 Thomas Charles Butcher 21 Anti Tank Bty. 106 Anti Tank Rgt.

VX71765 Bdr Terrence Richard Jones 21 Battery 106 Aust Anti Tank Rft.

VX71769 Gunner Ernest Henry Daw 21 Battery 106 Aust Anti Tank Rgt.

VX70801 Waler George Kellett 21 Anti Tank Bat. 106 Aust Anti Tank.

VX70783 Charles Andrew Field Hayes 21 Anti Tank Battery 106 Aust Anti Tank Rft.

V316382 Thomas Henry Skipper Home Forces.

SX1128 Sgt Harold Joseph Atkins 2/33 Battalion HQ Coy.

VX1235612 T H Pollard 21 Aust Anti tank Bty 106 anti Tank Reg 3rd Aust Division, could be Thomas Herbert Pollard Q151768 106 Tank Attack Regt, there is no VX1235612.

NX23953 Harry Brown 2/1 Aust Pioneer Btn HQCoy.

QX3150 Darcy Joseph O’Brien 2/33.

NX153191 William Charles Ford 7th Aust M.G. Batt.

NX154058 Allen Arthur Watton 7th Aust M.G. Batt.

QX4329 Robert William Ubank 2/7 Aust AAS W/Shop.

VX30297 Francis Clarence Schultz 2/2 Aust HY AA Regt W/Shops.

NX6485 Braund Leigh Grenville AACS FLD DET