Two years after their marriage, and now living at Taree, Dot and Guy’s happiness was shattered when her pregnancy resulted in her giving birth to a stillborn boy. Dot was unable to have further pregnancies, which further added to their despair. This terrible experience, I believed, had a life-long effect on Dot. Consequently Guy became very protective of her and spoilt her in any way he could.

No doubt living and working in town, for a bushman such as he, was foreign to his previous way of life and Guy found it difficult. One day at smoko at the milk factory a fellow worker and a person of dubious character, Bill Algie, ‘accidentally’ spilt some boiling water on Guy. The scalded man reacted in the way he knew best by punching and knocking the troublemaker to the floor. They were both given the sack, however Guy was offered his position back when management knew the full story, but Guy had had enough. It was his opportunity to break with this unfamiliar scene of domesticity he no doubt felt obliged to follow as a young provider for a family, a family that could no longer expand beyond husband and wife.

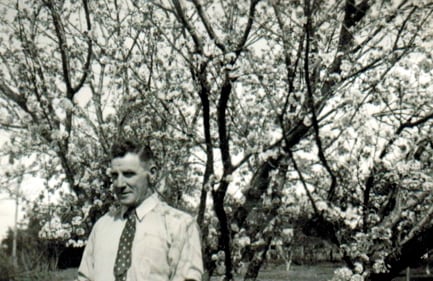

Guy went back to the land, becoming a share farmer at Wherrol Flat out beyond Wingham. That area was reasonably isolated in those days and during times of heavy rain the milk cans would have to be cabled high above the swollen creeks by means of what was known as a flying fox. Motor vehicles had difficulty in reaching the farm as the roads were very rough and the creek at the bottom of the hill on which the modest weatherboard house stood was a challenge to both driver and car. On one occasion my father’s work utility become caught half-way across the creek. My young brother Denis, Mum and I followed Dad, stepping through the moderately flowing knee-deep water and slippery rocks to the bank. We climbed up the hill and sought Guy’s assistance to extricate the immobile automobile. Both men freed the wheels and track of the large rocks and Dad drove the ute out of the creek and up the hill to the house.

When the Priors first moved out to the farm they found they had inherited a few white cats. Though never allowed in the house they made home around it and often created a nuisance by climbing onto the corrugated iron roof during the night. Once when the ladies visited the little house, which was always outside, they threw pebbles on the roof and laughed at the men and children inside cursing the assumed feline culprits. When the real cats were on the roof they were difficult to frighten away as they were unable to hear. Apparently it was common for white cats to be deaf.

Dad was always keen to pot a rabbit or two when visiting the farm. On one occasion he shot one with his shotgun on a creek flat (level ground was scarce in that area) on the other side of the creek from the house. Unfortunately, the poor animal was only wounded and sped off with its last ounce of energy. It ran towards a large blackberry bush with six-feet-three inches of Chris Woodland after him. Always behind the shooter – Dad was ever safety conscious – I was hot in pursuit. Dad was running into the late afternoon sun and next thing the most unexpected thing occurred and I saw him bounce back as though catapulted through the air, arms spread wide, holding his single-barrel 12 gauge Harrington and Richardson shotgun in one hand. He landed flat on his back as I noticed the fence wires that were difficult to see with the sun in one’s eyes. I dived between the wires and found the rabbit lying motionless on the edge of the blackberry bush. Had he expired a few feet further in he would have been unrecoverable.

Once when Guy dad in trying to pot a rabbit, he was carrying a common rifle at the time, a Lithgow Small Arms single-shot .22. He declared that he had a ‘six shooter’: One up the spout and five in his pocket.!

Chris, Denis and I crossed a little bridge over a creek on our way to the Wherrol Creek farm one day and Dad noticed a dead animal beside the road that had possibly met its demise by being hit by a motor vehicle. Bringing the ute to a stop Dad inspected the dead animal and found it to be a dingo. It was the first of my many sightings of the native dog through life and, by coincidence, it was at a stream bearing the name of Dingo Creek!

The life of a share farmer was a hard and poor paying one. The farmer worked the land for an absentee landholder and received little in return. In the late 1930s Dot and Guy told us that they received a mere £3 ($6) cheque for a month’s work. During the war the Australian Government assumed control of farm products bringing stability and better conditions and wages for many, including the dairy industry. Guy acknowledged their improved lifestyle was due to the Labor government, but said he could never vote for them as, ‘I am a country man’. He was a supporter of the Country Party, later to change its name to the National Party.