The day we went to Bunnamagoo was forecast to be a stinker – a genuine, east coast, January stinker with high humidity, high temperatures, and over the mountains worse to come.

Up with the birds, we’d made an early start – Ian and Jenny in their four-wheel drive, John, Dorothy and I, in the air-conditioned Honda – and there in the pregnant cool of early morning nothing could dampen our enthusiasm.

Our plan was a simple one, to follow the tracks of Sarah and James.

The first I’d heard of Sarah and James was the day my Aunt gave me the brooch. Sarah and James, she said, were her father’s grandparents, and on the day that they married, they had gone by coach to Rockley. There was not much more she could tell me, but Rockley, she thought, was west of the Blue Mountains, somewhere out of Bathurst. As to what was at Rockley, or why they went there, she had no idea.

Now these new great-great-grandparents captured my imagination right off. Maybe because we grew up with not much sense of family – no cousins, and just the two grandmothers who would no more talk about themselves than fly – but whatever the reason, I was hooked. I simply had to find out more about Sarah and James. Who were they? What was at Rockley?

So that is what this day was all about.

Giving me the brooch had clearly been something of “an occasion” for my fragile, white-haired Aunt. Under the light of the lamp on the small table beside her cherry velvet armchair, she had carefully positioned a dainty red and gold embossed box. Opening it gingerly, almost as if she might find something unexpected inside, slowly she peeled back a layer of yellowed tissue.

My Aunt told the story:

“Soon after Sarah arrived at her new home out there at Rockley, she found a gold nugget on their property. James, her husband, then had it made into a brooch for her. This, my dear, is that brooch. Your great-great-grandmother Sarah’s Brooch. You see the writing on it? And it’s been passed down from one generation to the next – Sarah Pye bequeathed it to her daughter, who gave it to my mother; then my mother gave it to me. And now it belongs to you.”

The brooch was unlike anything I’d ever seen. But not just quaint, or unusual, there was something else about it; something that reminded me of one of those old houses I might see on a late afternoon walk – one of those old houses that seems to hide a secret, seems to draw you, to whisper, “Come close and listen well, there’s a story I can tell …” Something you can almost feel.

So right from the beginning, this brooch seemed to have a story to tell.

Back home in Perth from visiting my Aunt, I’d checked the map, and there it was – south of Bathurst, at the junction of five roads, a town called Rockley. On today’s roads, no more than four hours from Sydney I’d guessed. Due to fly to Sydney again in the next few days, my schedule had no time to spare, but I’d have to get to Rockley somehow.

That night I phoned my east coast brothers, Ian and John. We planned a visit to Rockley. In the pit of my stomach, a gnawing feeling.

Restless night, and early morning saw the detective in me up searching through all my old documents again: birth certificates, funeral notices, photos, pages from old family Bibles, endless notes and newspaper cuttings themselves becoming pickled with age – in and out these many nooks and crannies so often now, that surely they had yielded up their every secret.

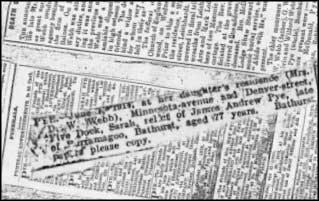

But there was one I hadn’t remembered seeing before – “Sarah… late of Burramagoo… 1914″ said the barely legible death notice squeezed in under yet another photocopy. Could this be my ‘Sarah of the Brooch’? Could ‘Burramagoo’ have something to do with Rockley?

“Has anyone heard of Burramagoo?” was my last-ditch query on the internet the night before my plane to Sydney.

The reply came promptly.

“Perhaps you mean Bunnamagoo. Bunnamagoo was one of the first pastoral land grants in the Rockley area out of Bathurst… some of the first grazing land to be opened up after Blaxland, Lawson and Wentworth discovered their way over the Blue Mountains… Lawson’s land grant also… .”

Greedily I made a print, grabbed my bag, and boarded the airport taxi.

My mind awhirl, rigorous evidence this was not, but “Breathes there a man with soul so dead…”? Could not this Bunnamagoo have once been home and hearth to our Sarah who found the gold nugget? My heart galloped ahead of the facts. After all this time, could some part of their old home be left still standing? Maybe there would be something, just something to show where they both once lived, had children, raised their family – even if it’s only small, part of some old stone wall perhaps, or even just an old tin shed.

And so today – almost 150 years behind our great-great-grandparents Sarah and James who took the coach to Rockley – as we leave behind the coastal plains of Sydney, a haze is rising, the morning has a dreamy feel, and Sarah’s coach trip fills my mind.

It’s 1855. The colony is young, Australia’s first Gold Rush is barely 4 years old, so this road we’re on isn’t the only thing that’s rough. Coaches are all heavily booked and we’re lucky to have even this single inside seat. James rides topside with our luggage – and his guns. By day, there’s heat, dust, and bushflies; by night, some wayside inn serves up doubtful food, flea-ridden bedding, and fitful sleep.

Dawn returns us to the ceaseless jolting of our coach with no springs. Steep and treacherous are the passes of these early rough cut roads; too rough a ride to talk much, but our company is a sturdy and resourceful lot, determined to make the best of things. Small privations these, we remind ourselves, compared to a generation ago when there was no coach, no inn, and nights meant just your blanket and the stars.

Along the road, groups of diggers trudge their way to the goldfields – hotchpotch groups on foot mostly, some with horse or donkey; streaming in from every corner of the earth, they’ve come to try for better luck than elsewhere, here in this ancient land unfolding out beyond the west divide. Here and there a convict gang sweats to fix this stony track never meant to carry such heavy traffic; while our wits are hourly whittled with the knowledge that these roads are infested with bushrangers – those carrion-like fringe dwellers drawn to easy pickings out here beyond the pale of law and order.

It was a journey with precious little comfort – perhaps no more than the ever changing tapestry of light and shade, of shapes and colours, of raucous sounds and wild perfumes of the untouched Australian bush. That, and their hopes and dreams for the future.

Today’s steep and winding modern mountain road so unlike the one that Sarah and James took, carries us swiftly up the eastern escarpment of the Great Dividing Range. The cool and dark deep green native bush haunted by calls of bellbirds is left behind us far too soon. Cresting the mountains, we pull off-road. Beside a park of oak and laurel, we freshen up with thermos tea and biscuits, ponder maps, walk briskly through rows of perfumed roses, and breathe deeply in the thinner mountain air.

First stage of our trip behind us now, ready for our descent into the rising heat of the western plains, destination Rockley, by group consensus Ian is to lead our little caravan – he, after all, has the map.

Lifetimes, now it seems, since we grew up in these mountains; since I looked out into this gentle landscape of pastel greys and blues, of yellows and greens; out into these wide expansive valleys, with their oceans of plains and distant rolling hills, with their softness of colour and form; a panorama where shapes and hues roll onwards and outwards, blend into each other and then on into nothingness – a timeless vista. The gods in private surely laugh as they watch us stumble to capture it on canvas, or film, or even here in words.

Was this a view that Sarah saw, and James?

I need some time to linger. But Bunnamagoo is calling, so we bundle ourselves back into our cars.

“So where are we going to now? ” Dorothy asks, and as we pull back onto the road, I try to explain.

“Well … ” I begin, but know there’s really not much sense to be made of it. “There’s this brooch I’ve inherited. And there’s this place out here somewhere called Rockley… And that is where my great-great grandparents came after they were married. And I want to see it, you see… Just to see if there is anything there to be seen. But whether we will find something there or nothing at all, I really have no idea … Well maybe we should write a poem about all this… ”

I try to sound jolly, but deep down suspect we’re on a wild goose chase.

The glare and the heat are incessant. No signposts, lots of dust. Even with our maps, it’s hard to tell which road is which out here. Mid-morning, and already we’ve used up most of our water. The air-conditioner has given up it’s struggle and it’s getting mighty sticky.

Wide this land, and hay coloured, close-up. Daubed with hazy outback blues and greens where streams or underground waters course – silent and aloof, a land that runs its own agenda. This road may not be the one we want, but the going – marked like all progress in this country, with swirls of rising dust – nevertheless makes us feel we are accomplishing something important.

A looming signpost, “Peppers Creek”. Beyond, a line of wooden planks bridge a sweep of scrubby trees.

“Rockley” says the second sign. Rockley!

Quickly we pull into the green-grassed village park beneath its welcoming umbrella of shady elms. Watered by its roadside river, this tiny old-time settlement with a handful of red-brick shop fronts and its single quaint old corner pub, is nothing if not postcard picture perfect. Sunday. It’s hot, but men who know what’s what, are hard at work putting in some effort to repair their pub’s verandah rail. Beside the small round table at the entrance, a weathered couple sport their hard-earned beers.

Now rolling up into a small town pub and asking for the name of some place mentioned in a 1914 death notice is a venture I’ve yet to experience; and as one to which I’m acutely aware there’s bound to be some risk attached, I half expect to be laughed straight out of town. Judging speed the better part of valour here – or perhaps because I simply cannot wait – I’m across the road, the pub verandah, through the door to the bar with my “G’day there mate, can you tell me where I’ll find Bunnamagoo?” before the family has time to know I’m gone.

My words hang in the air like out of season Christmas decorations. Suddenly I feel dry. The day really is a scorcher. The air is deadly still. The workmen on the verandah stop their sawing. I should have ordered a beer first, you don’t just roll into an outback pub and ask them where the gold is. I wonder if I have a fever.

“Well lady… ,” the fellow behind the bar drawls, looking at me hard. He raises up his right arm high. “Now why don’t you just take this road, this road right out front here, y’see? Y’take it right on outta town, out thatta way. Y’see the one goes thatta way?”

He lowers his arm pointing down the road.

“And then maybe ten kilometres out, you’ll see the old homestead.”

The old homestead?!

“The Old Homestead is still there!?” a voice with popping eyes croaks, or so it seems from where I stand.

“Well now lady, that homestead’s really not so old, now… ,” he drawls, giving me a queer look. “And you can’t really see it from the road, either. But you’ll know it when you’re there ’cause the name’s right on the mailbox.”

No Old Homestead!

From greatest heights my fragile hopes begin to fall. Quickly I turn to leave before my pain should show. But… and here one frail hope struggles up for life… who knows? Maybe there’ll be something out there anyway. Even if it’s just some old stone wall. Or just an old tin shed.

“But as for the Old Homestead … ” I quickly turn to catch the twinkle in his eyes. “… Well, you can’t see that from the road either.”

Ten kilometres pass like life before my eyes. And now an old grey stone convict-built homestead comes into view. Our wheels in concert, crunch upon a gravel drive. Slowly as a hearse, we round the bend to an oasis where the willows weep. Willows weeping softly round an old, old inner garden where the greening stit-stitting bursts of reticulation alternates with indolent cicadas droning in the heat of an outback summer’s day.

There, half draped from view – the Old Homestead. Modest and old fashioned, in her carefully manicured elegance, languidly, she seems to sigh … “Come close and listen well, there’s a story I can tell… “.

It’s where Sarah came with James. Bunnamagoo.

I can’t explain, but feel I have come home.

© Keri Webb

is a retired nurse, an artist and author with an interest in the lives and characters embedded in history.

Postscript:

James’ father, Tom Pye, established his Campbell’s River Farm, Bunnamagoo, in the late 1820’s to early 1830’s. It’s still a working property, though of a kind Tom would hardly have imagined in those times. Restored and cared for by it’s current owners, the Paspaley Pearling Company, it now produces cool-climate grapes and wines under the Bunnamagoo Estate label.

Further reading:

See Keri’s article – A Convict’s Lot