© Keri Webb

Step out of your Time Machine in downtown London in the 1780’s and it’s the smell that bowls you over! Worse, where the poorest people live, whole families are squeezed into a single room because it’s all they can afford.

You walk the higgedly-piggedly narrow streets past overcrowded lodgings – the air is dank, there are no drains, no garbage collection, no sewage, and it will be decades before poor sanitation, the cause of cholera and typhus, is understood and remedied.

With grinding poverty so common, it’s hardly surprising that theft is a way of life for so many – a contagious practice if you’re starving while your neighbour’s stealing is putting food on his table. So the usual sentence of death for everything from murdering the spouse to being caught with your boss’s spoon in your pocket is rarely a deterrent.

With so much theft, there’s hardly time or space to hang them all and jails are overflowing. Small mercies perhaps when the good King George – who is a really kind-hearted minor loony – hardly ever fails to commute your sentence of death to transportation.

Still that’s not the only problem. Until lately most British convicts were transported to the British Colonies in America. But since they’ve declared their Independence they adamantly refuse to accept any more British felons, and the question looms – where to send the convicts now? It’s nearing crisis point and a quick solution is needed.

Well then… why not Botany Bay?

Not long ago Captain Cook on his way back from mapping the transit of Venus in the South Seas, sailed up the east coast of the virtually unknown southland “New Holland”, and his reports sound promising.

The idea appeals because it would address two problems: the uneasy suspicion that if the British don’t settle there soon, then the French certainly will, and the need for an ideal place to send the convicts. While alternatives had been considered, as perfect a solution so far from ‘civilisation’ that the riff-raff won’t easily make it back to England, simply did not exist.

Well what happened to these poor unfortunates once they got there?

You could say it all depended. Some like Mary Bryant, convicted of robbery and assault, arrived on the First Fleet and wanted nothing but to get back home. Miraculously she did, and many books have been written about her amazing adventures.

Some like John Pye, convicted of highway robbery, arrived on the Third Fleet, saw before him a land of opportunity and went on to make something of a success of his life. And while most convict lives passed unrecorded, I was lucky enough to discover some of John’s story when I looked into our family’s history.

John was in his early 30’s when he disembarked at Sydney Cove. The year was 1791, the crops had failed and the colony was facing starvation. Two thousand newly arrived Third Fleet convicts severely worsened the situation. Quickly they were promptly sent off to work the land – some to Norfolk Island, or like John, closer inland to Toongabbie. As yet there were no horses or ploughs, no picks or shovels, no equipment to do all the backbreaking dawn-to-dusk work that was needed – trees felled and uprooted, native scrub to be cleared, soil to be ploughed, tilled, seeded, weeded and harvested.

Perhaps John Pye was lucky. He had a good head and was both capable and industrious and so it was not long before his efforts were rewarded with his own grant of 30 acres in an area that is now Baulkham Hills. Along with his wife Mary they worked their land and soon had a growing family.

Now it had happened that John had been transported on the same ship as George Best, another convict and one he’d formed a fast friendship with. In Toongabbie they secured adjoining land grants, and though John was no farmer he was good at organising. Best, on the other hand, was not only a farmer, but a good one.

As time passed the troubles and scandals of this unruly young colony whirled in the dust around them – the 1804 Irish rebellion “the Battle of Vinegar Hill”, the antics of the self-serving NSW Corps, and the 1808 Rum Rebellion when the infamous Governor Bligh who, it was said, had to be rousted out from hiding under his Sydney bed, to name just a few.

Then in 1810 came a significant change. The newly arrived Governor Lachlan Macquarie was “the new broom” sent to instil order in this seemingly uncontrollable colony. When he inspected the area, he reported (in his Scottish brogue if you can imagine) that:

“…Best and Pye, (were) two very industrious, respectable settlers who have their farms well cultivated and in most excellent order, with good offices, and comfortable, decent dwelling houses.”

Time passed, and John gradually added more and more land to his original grant and became one of several settlers in the colony responsible for successful cross breeding of sheep and the selling of meat, and wool for cloth to the Government.

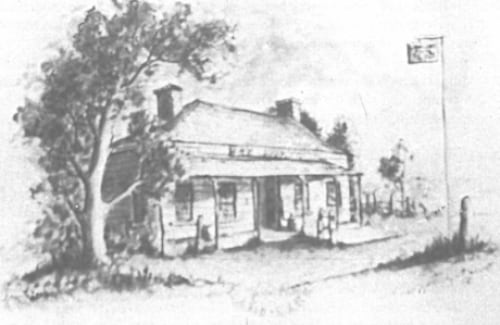

On his death in 1930 his successes meant he was able to bequeath substantial property to all of his family members. Included was a little cottage pub located on the corner of Windsor Road and Old Northern Road (now Seven Hills Road). Then, at this crossing of two dusty roads and seemingly in the middle of nowhere, the pub was known as the “Lamb and Lark”. Today it has evolved into a thriving local pub at Baulkham Hills known as the “Bull and Bush”.

It’s hard to know where to end these stories as they never seem to stop … There is John’s son Tom Pye’s adventures as he became one of the first settlers to seriously establish himself west of the Blue Mountains, as well as the escapades of notorious bushrangers and how they infringed on his life. There is the story of how life in the colony changed, not only with the building of roads, the coming of coach services, mail deliveries, banks, newspapers, and the opening of the roads to the south but also through the huge and often catastrophic effects of the 1850’s gold rush …

Stories probably best left for another time.

© Keri Webb

Keri Webb is a retired nurse, an artist and author with an interest in the lives and characters embedded in history.

Keri Webb is a retired nurse, an artist and author with an interest in the lives and characters embedded in history.

Read Keri’s article – The Day We Went to Bunnamagoo