© Ray Grieve

In 1975, I was in Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory, on the way to the Kimberley Ranges in Western Australia and waiting for a roadblock to open at midnight.

The Stuart Highway heading north was closed due to flooding at Newcastle Waters and the only other way was by the Barkly and Tablelands Highways. The police had set up the road block because the Tablelands Highway was an extemely narrow rough road, really only suitable for one-way traffic. At midnight the road was opened for traffic north and a small convoy of a few cars and three or four road trains were let through.

The police instructions were to get some extra fuel and go as fast as you can and to ‘not stop’, until you get to the Borroloola turn-off, about 500kms away. Imagine being told by a cop to ‘go as fast as you can’ on a straight road for that distance!

There were stories of road trains plowing into the back of vehicles if they stopped on the Tablelands ‘Highway’ . You couldn’t easily park off- road as there was long grass growing close to the edge on each side. The ‘convoy’ separated after a few minutes and we never saw the other vehicles until well after dawn and the Borroloola turn-off. After about 2,000kms and driving for around 30 hours from Alice Springs, it was into Katherine and then west to the Kimberleys.

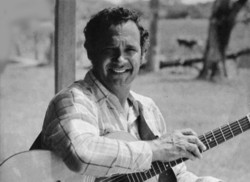

Eventually arrived in Halls Creek around midday. It was a hot, isolated town sitting on a flat red earth plain with no one in site. Eventually, I came across the local store which was owned by Ernie Bridge. Ernie greeted me and within a few minutes we were talking about music.

Ernie Bridge was a pastoralist , a local Councillor and ran a number of successful businesses in and around the town. We started laughing about how different our interest and careers in music had been. I had spent the past years since leaving school, playing in rock, blues and folk bands around Sydney , while he was born in Halls Creek and lived locally, with a love of country music, particularly Slim Dusty. He had a good local reputation as a bush ballad and country singer. He said “Well, you’ve come all this way and you’ll hear the number one hit up here at the moment -Ted Egan’s “The Drinkers of the Territory”. It was playing on the radio, everywhere around the Top End and everyone loved it.

He noticed my interest in a beautifully- crafted didgeridoo sitting in the corner. It was made from a bloodwood tree with a carved mouthpiece and three charcoal rings on the end. Ernie said “I’ll go and get the bloke who made it” and came back with Matthew Dembal Martin. He was a young stockman about my age from a cattle station near Derby who was visiting Halls Creek.

He was a member of the Ngarinyin and Wunambel people. Ernie was a bit older. We sat on the floor and he told me how he had actually made the instrument, including the process of filling a knot- hole with gum resin amongst other fascinating details and we settled on a price. An instrument such as this was not common back then, as they are now. Now you can buy one anywhere, but in 1975, this was something special – a proper didgeridoo.

Ernie Bridge suggested camping that night at his property next door. It was a completely barren open red dusty area, which he used as the local picture theatre. He would cordon off the area and set up a screen and projector and the customers would bring their own chairs or sit on the ground (and hope it didnt rain). I later saw a photo of the theatre somewhere with a big sign outside, advertising that Buddy Williams would be playing there soon. So it must have been used as a venue for visiting performers as well.

Looking back years later, I couldn’t help but think what a strange meeting it was: three people with a completely different futures ahead. Within two years, Ernie Bridge would start a successful performing and recording music career as a country and bush ballad singer. In another three years he became the first Western Australian indigenous member of Parliament and then Government. He was awarded the OAM and AM medals. Matthew Dembal Martin became a founder of the Junba Project in collaboration with the University of Melbourne to preserve, document and teach his culture to future leaders.

He is now an Elder, Lawman and song and dance Junba Leader and Cultural Mentor at the Mowanjum Art and Culture Centre Western Australia. While my own endeavours were not quite so grand, I could never have guessed that I would not just continue to play music and form bands, but eventually undertake a project of many years of research and writing, on the history of the mouth organ in Australia. A study which would include a completely different kind of ‘boomerang’.

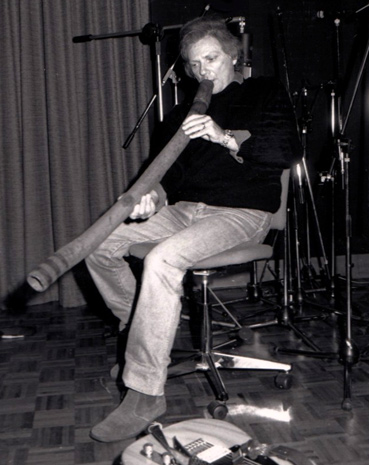

I kept ‘Matthew’s didgeridoo’, as I always called it, at home but never played it in public. I began to realise that owning an instrument after having met the actual maker, was starting to mean a lot to me. I looked after it well but couldn’t work out how I should fit it in with the music I was playing at the time. Practising circular breathing was beneficial to my flute playing – it’s always good to have plenty of lung power, but in other ways not so beneficial. I found that after a good session of didgeridoo playing, my lips were sort of numb and I couldnt concentrate on the flute embouchure for a good tone. Keeping the two instruments apart was the answer. Nothing worse than having a flute and a didgeridoo in conflict with each other.

I started recording tracks in my Bushlark band with Jeff Todd many years later and became aware that Matthew’s didgeridoo seemed to be getting annoyed that I hadn’t used it in the studio. So I took it to the session, on the day we recorded “Tasmania”, a piece using traditional Tasmanian- themed folk songs and I decided to use it as a background for a flute solo segment. Most flute players know that if you play a flute you can probably manage a saxophone. Physically different of course but otherwise pretty much the same technique. Being involved in folk music meant that I never bothered with the sax, but had always listened to sax players from the 1940s on old recordings and loved the music. One of my favourite players was Tommy Dorsey of the famous Dorsey brothers jazz bands of the era. He sometimes used a strange staccato, almost awkward style of playing, which really worked. The idea suddenly came to me and I played the”Tasmania” flute segment in that style,with the didgeridoo behind it, though not pretending for a moment to be a jazz musician.

Later in the day, a very big red-bellied black snake was seen outside the studio. It had tried to get in a back door which was in a wooded bushy area. Someone from another part of the studio rushed outside and killed it – unfortunate and wrong in retrospect, but it was big and very close and we all freaked out. So the day ended with a potential snake attack and a Tasmanian folk song featuring a didgeridoo – even though indigenous Tasmanians didn’t use didgeridoos and the fact I had played a solo inspired by an American jazz saxophonist! I was happy with outcome but something still wasn’t right.

In 2019, with didgeridoos by now used in all sorts of bands both locally and overseas, or sometimes to just proclaim ‘Austraya,’ I knew that it had to have some tracks of its own – to be treated with more respect perhaps. So I wrote “Harmonic Connection” in collaboration with Stephen Lindsay, a fine keyboard player and owner of Oceanic Records and “Ant Rythm”. They were both written for Matthew’s didgeridoo , with a deliberate blending and fusion between flute and didgeridoo. My son Lyall is on guitar along with keyboards by Stephen and Dave Clayton and Nick Churkin on bass and drums.

I never got in contact with Ernie Bridge again – he died in 2013 but in talking to Matthew recently, we planned to catch up one day – hopefully soon. As for Matthew’s didgeridoo – its standing and resting quietly in the corner and seems to be happy now. After so many years, the connection has been made.

© Ray Grieve

- Read our interview with Ray.

- Visit Ray’s website.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Ray Grieve was a vocalist and rhythm guitarist in 1960s Sydney rock and blues bands including the Elliot Gordon Union. He played flute and tin whistle in traditional Australian folk bands and was one of the founding members of The Rouseabouts within the Bush Music Club in the 1970s.

In 1981 he began the research and collection of material on the history of the harmonica in Australia. The result of this research was his book, A Band in a Waistcoat Pocket, and the companion tape and CD sets. He has subsequently released a number of CD albums with his band Bushlark.