© John Low

AN INTERVIEW WITH RAY GRIEVE

Ray Grieve‘s early musical experience was in the rock world. He began singing professionally in 1964 and, throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, was lead singer in a number of rock bands including the Minit-Men, the Travellers and most notably the Elliot Gordon Union. Between 1966 and 1970 the EGU was one of the more popular bands performing around the Sydney area and they regularly shared the bill with such acts as Taman Shud, Flying Circus, Masters’ Apprentices and the Dave Miller Set.

When the EGU called it a day in 1970, Ray went to Adelaide and joined the popular South Australian band W. G. Berg, which upon his arrival metamorphosed into War Machine. However, their career was short and after playing at the three-day Myponga Festival in January 1971 the band broke up and Ray quit the music business altogether. During his time out he developed a passionate interest in Australian traditional music and when he decided to re-enter the music world it was the folk arena he chose.

Ray joined the Bush Music Club and became a foundation member of the popular and highly regarded bush band the Rouseabouts, which played around the Sydney folk scene in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

He has subsequently released a number of flute solo singles and a CD album and completed a major research project (book and CD/cassette package) on the harmonica in Australia.

THE INTERVIEW

After such a long association with rock music, what lead you to an interest in Australian folk music?

After the demise of War Machine I spent five years outside of the music scene and lived a very different lifestyle. Aside from getting married and having a normal day job, my wife Raema and I travelled around and across Australia in a number of trips in our van. As I was not committed to playing professionally, I had a lot more time to explore all sorts of music, from all the familiar forms of rock to folk, jazz and classical. However, our trips throughout the outback gave me the inspiration towards one particular category, that of Australian traditional folk music. I had hardly known it existed until I heard small segments both live, through some folk music enthusiasts and friends and on country radio occasionally while we were actually out there.

On one occasion in 1975, we were in Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory on the same night that Warren Fahey and the Larrikins were playing there. I decided to hang around a bit, introduce myself to Warren as a good regular Folkways customer and see if I could get up and play along with the Larrikins. Apparently, however, there had been a lot of trouble in the town that night with drunken fights and brawling and the cops moved us on twice, with a warning not to come back. The audience appeared to be very well dressed local property owners or dignitaries and I don’t think I would have got past the front door anyway, especially in the way I was dressed. We had been travelling for weeks around the Territory!

Country music sounded too American to me, not much was heard of any sort of Aboriginal music at this time and, after faithfully performing mainly US music in my previous bands, Australian rock or pop music didn’t sound any different to me from the American or English equivalents. It came as a surprise to discover that there was actually a traditional Australian music form.

While I would always retain a love of the rock music I grew up with, the experience of hearing Australian traditional folk music at various times while on these outback trips changed my musical direction completely. Although I did not intend to ever play professionally again, I decided to get a few instruments together to play for my own amusement at home.

In your earlier life you’d been primarily a vocalist. What were the instruments you decided to take up?

I had been told that my Grandfather played the tin whistle a bit and in fact I had his old one, so for no particular other reason that instrument became my first choice. I bought a range of new English Generation whistles and eventually a new hand-made Smart wooden flageolet from America. I also restored an old Ecko semi-acoustic electric guitar that Gary Lothian (ex Elliot Gordon Union) had given me years before. I had played it a bit in my rock bands, but now decided it would be worthwhile restoring it properly. What I really needed, however, was a fully acoustic model, so I bought a good quality new Japanese Aria guitar.

Later when I was preparing for professional work, I thought I had better expand my musical instrument line-up and taught myself to play the bones and the spoons. The spoons were acquired from our kitchen but the bones situation was a bit more complicated. Although plastic ones were available, I did it the truly traditional way by getting some from the butchers, drying them out, filling them with resin for the right acoustics and polishing them.

Over time, as my playing on the tin whistle improved, someone suggested I try the flute and I managed to buy a cheap old Buisson model which I then went on to learn. A lot of my energy went into learning and playing the flute, so eventually I didn’t bother contributing further with vocals.

About 1978, during my time with the Rouseabouts, I replaced the old Buisson flute and bought a new Japanese Hernals concert model with silver plated head. I also managed to find some old wooden flutes and flageolets at the premises of a second-hand dealer in Leichhardt and had them restored. I had special cases made for the three concert flutes. These flutes were at least 80 years old and comprised English, French and German models.

How did you become involved with the Bush Music Club?

Living in a number of units in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, playing at home had its limitations, so I decided to check out a few venues where I could get together with some folk musos and have a few jam sessions.

I visited a number of known folk venue pubs in the first part of 1977. One of the best was in Harris Street, Ultimo, where quite a few musicians gathered every week. I remember seeing Keith Snell, Len Neary and Declan Affley all jamming there before I knew who they were. One night they had Morris dancers performing in the street outside, in a little dead-end cul-de-sac next to the pub. Some time later this pub became a French restaurant.

By mid-year, word-of-mouth led me to the Bush Music Club where anyone was invited to join up for a small annual fee and, as members, come along on a week night to jam in their weekly meeting place, the Community Hall in Burwood. I was particularly keen to join this organisation rather than the other clubs that were also operating because the BMC was the only one that promoted and played strictly Australian traditional music. That was important in my quest, whatever that quest was. The others seemed to be influenced largely by Irish/Scottish/English folk and there were also American bluegrass and blues organisations.

However, the Chieftains were becoming popular worldwide and a huge interest was growing in Irish folk music generally. And, of course, there was no escaping the Irish influence because it played such a big role in the original development of Australian traditional music.

Perhaps because of this new popular folk movement, the BMC was undergoing a resurgence at the very time I joined up. After its formation by the cast of “Reedy River” and the Bushwhackers in 1954, the Club had had its ups and downs over the years. But now they were in the process, mainly through Dave Johnson, of forming a new Concert Party Bush Band to take on professional engagements and a quarterly newsletter, the “Mulga Wire” edited by Bob Bolton, had just been introduced. Within a week or two, I joined the band and Raema was asked to contribute illustrations and artwork for the newsletter.

So, as a tin whistle, bones and spoons player and rhythm guitarist/backing vocalist, I was ready for my first professional engagement in around six years.

What sort of gigs did the Concert Party Band play?

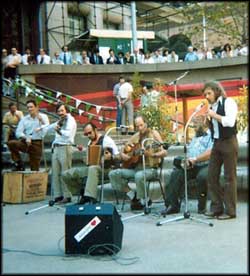

The first gig for the BMC Concert Party Band was about mid year at a Saturday morning markets/festival in Foley Park, Glebe. We played there again a few weeks later as well as about ten or so other engagements around Sydney before the end of the year. We also played at Lawson in the Blue Mountains and ended with a late night jam session evening in the Leura holiday home of some Club members.

The most interesting engagement was for the International Day Concert, a sort of precursor to Carnivale. It featured a line-up of bands and acts from many countries around the world with us representing Australia, naturally enough. The Federal Minister, Al Grasby, was the main official guest, along with Franca Arena and others. They gave us a special ‘finale’ spot and a huge applause as the host or home country and Al Grasby asked us a lot of questions about traditional Australian music. It seemed that everyone wanted to learn more about it.

How did it feel to be playing professionally again?

It was all a complete learning experience for me and I didn’t mind at all that the money we earned went to the BMC. A learning experience for me too was playing in an acoustic band. After my former years in bands of incredibly loud volume, I found this situation very different and rewarding. For instance, to be able to play a whistle or flute solo softly over an acoustic guitar was totally new to me and probably convinced me I was now back in the music business to stay if it was at all possible.

The quality of the Concert Party Band, however, depended on just who was playing at the time, as the member line-up changed frequently. There were usually a few experienced core players, but generally it was made up of amateurs who came and went. I was never sure where I fitted in. I was certainly experienced but not necessarily in folk music. I recall seeing a few people who recognised me from my rock days and who looked totally amazed at my new place in the world of music.

By the end of the year I hadn’t made any plans to change things much because I kept discovering that there was always a new jig, hornpipe or reel to learn and that was enough to keep me going along quite happily for the foreseeable future.

But eventually you found yourself in the Rouseabouts, a more professional band. How did this come about?

At a BMC meeting late in 1977, Dave Johnson raised the possibility of forming a band that would operate on a more professional basis than the existing Concert Party Club bands had been capable of doing. Five players, including myself on flute, tin whistle and acoustic rhythm guitar, were chosen to form this new acoustic traditional folk band. The others were Dave Johnson on vocals, banjo and guitar, Keith Snell on concertina, John Poleson on button accordion and Bob Bolton on harmonica. Except for me, they had all had a good deal of experience in folk and bush music clubs and groups.

The name Black Velvet Band was chosen and we did our first booking at a backyard shed/barn bush music dance at Dural in Sydney. For our next performance at the beginning of 1978 we became the Rouseabouts, with a subtitle, ‘The Rattling Good Bush Band’. Keith Snell soon began to show great expertise as a booking agent and secured a lot of bookings for us which, along with our BMC gigs, kept us constantly in work.

John Poleson, who was a ranger at Neilsen Bay, Vaucluse, for the National Parks & Wildlife Service also got us bookings at their functions. Through this, the NP&WS allowed us to use a room in historic Greycliffe House at Vaucluse, which was undergoing renovation by them, for our weekly practices.

Could you give us some idea of the band’s performances?

We dressed in ‘traditional’ colonial style gear, which included moleskins, waistcoats and scarves, and for our repertoire chose as many Australian traditional dance tunes as was possible. Otherwise we played known traditional Australian arrangements of Irish or Scottish tunes. These comprised jigs, hornpipes, reels and waltzes. For the remainder, Dave sang traditional Australian folk songs.

It was a good time for a band like this as Australian traditional music was enjoying a surge in popularity and we were assured of lots of bookings. Most similar bands at the time were mainly vocal/instrumental outfits, but we concentrated on an 80% instrumental format and promoted traditional dancing which Bob Bolton was able to call. When we had a big function that promised a huge crowd we were able to get John Knyvette, a professional caller and dancer, to do the job. He was able to get down with the audience, choose a partner and give a demonstration to get everyone started properly.

The reaction to traditional music at some functions was amazing. People got so much enjoyment from it, we were called back for encores many times by enthusiastic audiences who couldn’t get enough of it.

At what sort of venues did the Rouseabouts play?

We appeared at the annual Rocks Procession that required us to play on a float through the city and into the Rocks area where we gave an open-air concert in the park with Bernard Bolan and other artists. Soon after, we played at weekly dances with other bands at Balmain Town Hall and a Sydney Harbour cruise for the NP&WS for the delegates of the 2nd South Pacific Conference of National Parks and Reserves. Government members of various South Pacific islands and nations gave a performance of their own traditional music after listening to ours. For the following three years we played at the Marble Bar in the Sydney Hilton for St. Patrick’s Day and lunchtime performances in Martin Plaza.

To give the band a stronger sound, Bob Thompson on fiddle joined up and by mid-year the Rouseabouts had its own folk club, which was largely organised by Keith. This was the Colonial Folk Club held upstairs every Friday night at the Gresham Hotel on the corner of Clarence and Druitt Streets, Sydney. It ran for a few months but disagreements between Keith and the hotel management finished it off. We had good crowds every week and generally it was very successful for the short period it lasted. Eric Bogle was one of the guests.

Dave announced that he would be leaving the band in the near future to concentrate more on his BMC activities and out of which he formed another group, the Reedy River Bushmen. Because of this we recruited some more members, Len Neary on vocals and tea-chest bass and Chris Kempster on vocals and guitar. Chris was one of Australia’s legendary ‘folkies’, having been an original member of the first bush band in modern times, the Bushwhackers, formed in 1953 from cast members of the original production of the play Reedy River.

Our bookings remained consistent over the three years or so that I was with the band. They included the 1st and 2nd Colonial Subscription Balls held in Sydney for the BMC, a NP&WS dance at Caves House, Jenolan Caves, and many other concerts, dances and functions. We also played at the Sydney Opera House Forecourt for the Festival of Sydney and in Hyde Park for Australia Day and if ever one of our members couldn’t make it we could always get a replacement for the day from the ranks of the BMC.

We played a large number of country-dances too, including Sofala, Hill End, Bathurst and Carcoar, that drew hundreds of people. At Sofala the crowd was so big and the hall so small that each time we played there we would have to rig up our extra speaker system outside the hall for the huge crowd to dance to in the street.

Was it in 1978 that you participated in the re-opening of the historic Hartley Village on the western edge of the Blue Mountains?

Yes, in August 1978, we were approached by the NP&WS to provide a segment of music relating to the history of the crossing of the Blue Mountains for the newly restored and renovated Hartley Village. It was recorded at R. D. Barlow Pty. Ltd. in North Annandale. It comprised vocal and instrumental offerings which were edited into an audio-visual slide presentation around a separately recorded oral history of the event, running for around 30 minutes. This audio-visual display was for permanent showing to tourists in a small theatre room in the old Rectory/Presbytery building in the village.

We were also booked to play at the Opening Day Ceremony at Hartley Village on the 14thAugust. The State Government had spent a lot of money on the restoration and there were many dignitaries, politicians and local identities present on the official guest list.

It was a hugely successful day all round with great weather as well. Our transport from Sydney and back was arranged and we played all day in the open outside the old Courthouse. Inside the Courthouse there was also a permanent audio presentation featuring Declan Affley among others. The Opening Day event was covered by the Sydney Morning Herald and local Lithgow press and on ABC TV and Prime TV from Orange. After a photo session with the State Minister Mr. Crabtree, we were invited to call in to the local apple orchard shop of Barry Morris on the way home to collect a bucket of apples each.

The audio-visual ran for another 7 years or so in the old Rectory/Presbytery building and was then transferred to the old Post Office building after it was partially restored around 1985. It ran there for another 10 years or so, until it was water-damaged after a bad storm. It is now housed in the Farmers’ Inn.

The band also recruited another high profile ‘folkie’ in Declan Affley?

Due to our contacts and Keith’s management skills we continued throughout 1979 to 1981 with quite a heavy workload compared to the average bush band of the time. Bob Bolton, who had strong connections with the BMC left to work with other bands and projects in that area after having a disagreement with Keith and Declan Affley joined us. An Irish/Welshman, Declan played fiddle, guitar and did vocals and was very well known in the folk scene. He had put out a couple of solo albums and had worked for the ABC as well. Declan left the band after about a year with us to concentrate again on his solo work.

Is it true that the Rouseabouts had something of a reputation as a ‘drinking’ band?

Well, with Declan’s arrival, the Rouseabouts’ reputation as a heavy drinking band was strengthened. It became quite a regulation that whenever we played there would always be dozens of cans of beer supplied from somewhere or someone. It was said that the band usually sounded pretty bad up to about half way through the night until we got about half way through the supply and then things really started to move along.

There was a problem when we played for the Methodist Church at their Vision Valley Youth Camp, a gig that strictly prohibited alcohol. That didn’t deter us because our supply was smuggled in and consumed secretly, but we had a problem of how to dispose of the dozens of empty cans at the end of the night. One of the band quietly sneaked into the chapel which was next to the hall where we had played and stacked them all neatly inside the pulpit. They only just fitted in apparently and were ready to topple out at the slightest movement. We couldn’t help but wonder what would happen early the next morning, a Sunday, when the service began.

Unfortunately, then we couldn’t remember where we parked and spent almost an hour or so wandering through the bush around Vision Valley, until we found our cars at around 1am. At one stage Declan dropped his fiddle somewhere in the bush so we all went back to look for it.

Another alcohol-related problem was caused by our ‘roadie’ Rick who we called ‘The Ulladulla Kid’. One night after he had had a few too many at one of our Marble Bar St. Patrick’s night performances, he started a fight with the bar manager. The manager was almost knocked out cold and we were not booked for future St. Pat’s nights after that. Many years later Rick stood unsuccessfully for election as a Democrat in his South Coast Ulladulla electorate.

I had an unfortunate incident of my own (non-alcohol related), which left very painful memories. The band always used a PA system and mics that were owned by Keith and one night he left it all at our place at Lilyfield. I stacked it in our hallway and, on getting up after midnight to visit the bathroom, walked straight into it. I broke a small bone in my foot, which healed itself but the pain was unbearable for weeks and I had to use crutches for a while.

What do you feel you gained, both musically and personally, from your time with the Rouseabouts?

Being a part founding member and playing with the Rouseabouts was a very rewarding experience for me. Although it could never be claimed that we were musically brilliant, we did manage always to get the audience up and dancing and having a good time. Such was the popularity of bush music, we usually always scored a number of encores and always left the stage to lots of applause. Like most bands we had a few disasters, mainly due to taking corporate or formal bookings that didn’t suit us because we were a very laid back casual group.

Personally, I learned a lot from the band. I was a relative newcomer to the folk scene when I got the opportunity to be involved and especially to work with such experienced players as Declan Affley and Chris Kempster. I also learned a lot of music from Keith Snell and Bob Bolton’s extensive folk music repertoires.

Many of the performances we did had social relevance and were much more meaningful and valuable than any I did in my many years in the rock scene. We played for many worthwhile causes such as Operation Noah to raise funds for NP&WS projects, the Students for Australian Independence Movement and the Walk Against Want Campaign to name a few.

I understand it was also through your involvement with the Rouseabouts that you began researching the history of the harmonica in Australia?

Yes, aside from being able to develop and improve my own flute playing in a professional environment, it was through the Rouseabouts that my introduction to the old records of Raema’s step-grandfather, P. C. Spouse, came about.

Bob Bolton, being a harmonica player and BMC identity, had received a taping of them from John Meredith and hearing them was the catalyst for my many years of research into the history of the harmonica in Australia. Five years of playing traditional music had given me a real passion for Australian music history and I formulated a project to research, collect and preserve rare items of music from the past. The end result of this was the book, A Band in a Waistcoat Pocket: the Story of the Harmonica in Australia, published by Currency Press in 1995.

This eventually resulted in your departure from the band?

I left the Rouseabouts around the end of 1981 when it became clear to me that I would have to devote my energies, normally reserved for playing, to doing serious and solid research. They replaced me with folk-singer and guitarist Sonia Bennett and kept going for another 2 years or so.

When Keith decided to move with his family to Perth, a decision was made to break up the band and we were invited to a Rouseabouts Farewell at Keith’s place in Kings Langley, a very enjoyable jam session which brought back a lot of good memories.

Declan Affley died in Sydney in 1985. Keith Snell died in Perth in 1998. It was his intention at the time to visit Sydney and organise a Rouseabouts Reunion Concert.

RAY GRIEVE’S RECORDINGS ANDD PUBLISHED WORKS

1967

Elliot Gordon Union, band and vocal rock tracks, un-issued

1978

Rouseabouts, soundtrack for National Parks and Wildlife Service’s audio-visual presentation for public screening at Hartley Historic Village, NSW.

1981/1982

Small issue archival recording productions on 45 and 33 1/3 rpm: Nolonger Available

1989

“Reedy River”/”The Rights Of Man” (flute solo instrumentals) 45rpm single (Bushlark) N/A

1990

“The Exile Of Erin”/”The Yarmouth Reel” (flute solo instrumentals) 2 tr. cassingle (Bushlark) N/A

1995

“A Band in a Waistcoat Pocket” (The Story of the Harmonica in Australia) 130pp. book (Currency Press)

Researched and edited by Ray Grieve.

“A Band in a Waistcoat Pocket”, 2 vol. CD Set, Larrikan/Festival/Mushroom records

Historic Australian harmonica recordings.

Produced by Ray Grieve.

“Australian Harmonica History”, 4 vol. Cassette Set (Bushlark)

Historic Australian harmonica recordings.

Produced by Ray Grieve

2000

“Reedy River Flute” (flute solo instrumentals) 10 tr. CD (Bushlark)